The Housing Crisis is an Anglosphere Phenomenon

Plus Inflation Narratives, Subsidy Arms Races and Top Tweets

What’s the New Idea? 💡

The Housing Crisis is an Anglosphere Phenomenon

When we discuss the Housing crisis in our country, the temptation is always to look for local causes. A specific policy, a cultural attitude, a group of local objectors that is unique to our part of the world.

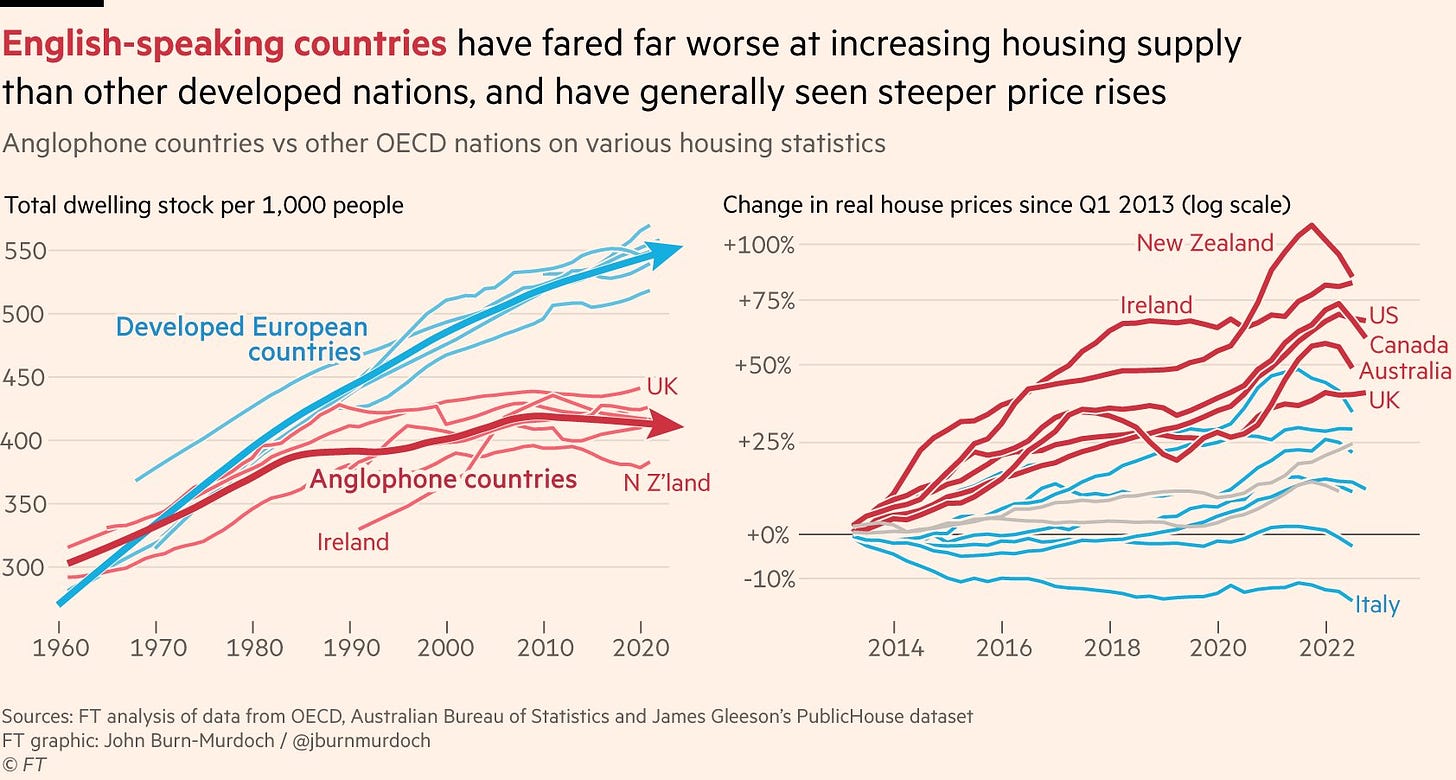

This analysis, however, isn’t always supported by the data. On housing, when we look across a whole host of countries, the pattern looks incredibly similar - home building dramatically trailing population growth and house and rent prices far outstripping wage inflation.

This same pattern is present in *some* countries, but not others. So instead of wondering what individual countries have been doing wrong, we should be seeking the defining characteristics of countries who face the same problems as us. To me, the most coherent group seems to be the “Anglosphere”. The US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and us.

John Burn-Murdoch published a great piece of analysis in the Financial Times this week, offering some suggested reasons why the anglosphere might be struggling with housing policy.

He places much of the blame on our distaste for apartment living. The cultural significance of the standalone family home and the facilitation of objections to new apartment buildings across the anglosphere.

“Across the OECD as a whole, 40 per cent of people live in apartments, and the EU average is 42. But that plummets to 9 per cent in Ireland”

I’m not sure if his focus on apartments tells the full picture, but his framing of the problem as an “anglosphere” one is spot on. Here are some additional hypotheses on why the anglosphere stands apart:.

Seán Keyes at TheCurrency.ie: “My pet theory is common law derived planning in Anglophone countries (more uncertain) vs Napoleonic planning in Europe (less uncertain)“

Many, including Venture Capitalist Brian Caufield noted the “Differential in net immigration between Anglophone and other countries“. We have strong economies that need to pull in workers, causing population growth to outstrip housing growth.

Twitter user firebrand Dove shares her theory that there are two, separate drivers in different parts of the anglosphere: “US/Aus/Can went for low density because so much land was available. The UK suburbs and the greenbelt were the opposite: a reaction against Victorian era slums. ”

And for balance, there are many of course who feel this is a positive and correct attitude to have towards apartment living. American houses are dramatically larger than Italian apartments. James Morrow of Australia’s Daily Telegraph captures this view as “God forbid people don't want to live in high-rise human filing cabinets.“

Lots of good hypotheses for testing and a good reminder that the solutions we’re looking for are broad and systemic, not local or personal. The main thing to watch for is when one of the anglosphere countries diverge from the pack so that we can pay close attention to what they changed.

Trending News Narratives 📰

Economic news narratives, in summary and context.

1. Corporate Greed Drives Inflation

As mentioned here before, “Corporate Greed is Causing Inflation” has become the most cohesive narrative to counter the notion of a “Wage Price Spiral”. It lacks some nuance - some corporations have always been greedy, but supply constraints allow them to exercise that greed through price hikes - but is still an effective counter-balance to the notion that wages are the leading cause of inflation.

Supporting this narrative, The Financial Times published data from Professor Isabella M. Weber showing that “profit margins of US companies have reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the second world war.”

“Having made windfall profits on the back of commodity price fluctuations and supply bottlenecks, large companies have been emboldened to raise prices further to increase profit margins. They found that there was little evidence that the models used to explain the inflation of the 1970s — such as excess aggregate demand, money supply expansion or increased wage costs that prompted a spiral — applied to this recent rise.”

2. Price Rises in the Fog of War

Samuel Rines has another explanation for this narrative - not only are corporations using supply constraints as their lever to raise prices, some companies are also using the “fog of war” to raise prices. As he explained on a recent odd lots episode, using Pepsi as an example, there are two overlapping factors:

When western sanctions were placed on Russia, companies could no longer sell there and instantly lost about 4% of their revenue. Not wanting to report a loss to their shareholders, they decided to increase prices everywhere else, to make up for the sales shortfall in Russia. They could do this with some confidence, knowing that all their competitors also had Russia-sized holes in their sales and would likely increase prices too.

In an environment of high inflation, consumers tend to get less price sensitive. You notice the price of pepsi has increased, but instead of shopping around for an alternative, you just shrug and assume it’s the same as everything else. In the “fog of war” of high inflation, we find it very hard to tell if one brand has become more expensive than their competitors, because we don’t remember what anything costs any more.

The evidence for this comes directly from the earnings calls of many of these companies, who have found a surprising (even to them) ability to increase prices without a decrease in sales volumes.

Bloomberg: “Companies Are Telling Us the Real Reason They're Still Raising Prices” Link ($)

3. This Ain’t Industrial Policy It’s a Goddam Arms Race

In response to China’s growing economic strength, the United States, under both the Trump and Biden administrations, is pursuing an economic agenda that combines robust industrial policy with a worrying amount of protectionism and import substitution.

The mammoth Inflation Reduction Act, for example, seeks to drive innovation and development in climate technologies that would otherwise suffer underinvestment or delay (this is good), but with a significant risk that the funding just ends up providing subsidies and tax breaks to existing technologies already on their way to scale.

For example, Volkswagen are being tempted with $10bn to locate battery factories in the US instead of the EU. This wouldn’t get the world more batteries, just change where they’re produced.

Europe is now deciding how to respond to this. Should the EU respond in kind with its own suite of subsidies?

This is one occasion where I think the conservative economic approach is better suited - leaving some potential upside on the table in favour of minimising risk. It's exactly the kind of perspective you'd miss having championed in the room since Brexit.

The EU’s long-standing ban on “state aid” has at times been overly restrictive, but on the whole kept protectionist instincts at bay and supported the fair, open single-market. As the US pivots towards protectionism, it will be interesting to see how the EU manages to thread the needle of being open without being naive, and being supportive of industry without becoming beholden.

Economist: The battle for Europe’s economic soul Link

FT: VW puts European battery plant on hold as it seeks €10bn from US Link

Irish Times: Ireland leads rebellion against EU ‘industrial subsidies race’ with US Link

📊 Public Opinion

Research and Data on people’s economic beliefs.

Inflation Worries the World: Rising prices is a concern for four in 10 (42%) people, on average across 29 countries. Inflation has now been the top global concern in the IPSOS “What Worries the World” survey for the last 12 months. Link

No Banking Panic. In the US, most Americans trust that their bank is stable, and their deposits are safe. Only a bare majority of Americans are tuned into the Silicon Valley Bank failure. Most, particularly lower income Americans, aren’t following that news. Link